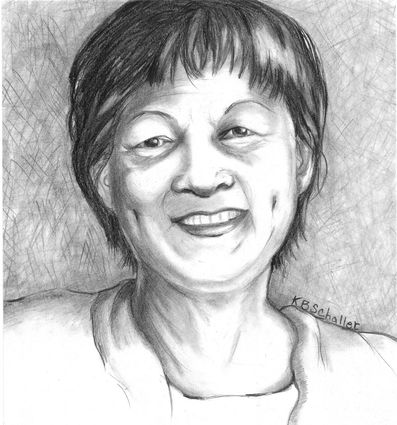

Alaska's "Rosa Parks": Alberta Schenck (1928-2009)

Eskimo Civil Rights Protester

Last updated 3/15/2015 at 3:24pm

K.B. Schaller

Along with Alberta's courage and the crucial testimony of Elizabeth Peratrovich, such statements helped to stir the collective conscience and contributed to the passage of the Alaska Anti-Discrimination Bill, which penalized racial discrimination in Alaska long before the Civil Rights movement took place in the rest of the nation. In 1955 when Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white patron and sparked a bus boycott in Alabama, Alberta Schenck was belatedly honored as "the Rosa Parks" of her people for her courageous fight for equal rights. In 2011, Alberta Daisy Schenck was inducted into the Alaska Women's Hall of Fame.

Alberta Daisy Schenck was born in Nome, Alaska, to Albert Schenck, a Euro-American Army veteran of World War One, and Mary Pushruk-Schenck of Native Inupiat heritage.

Although Alaska was purchased from Russia by the United States in 1867, it did not enter the Union as the 49th State until January 3, 1959. Like the whole of American society in that era, prejudice against people of color and racial discrimination were the practices of the day.

In 1944, as a 15-year-old high school student, Alberta Schenck-along with her class-was studying about the Constitution, the United States Civil War, and President Abraham Lincoln's freeing of the slaves. It made her think of the similar unequal treatment of her Eskimo people by Euro-Americans.

Alberta also had a personal interest in the struggle for equal rights. As a part-time usher at the Dreamland theater, her duty was to make sure that Native Eskimo people did not sit in the "white" section, even if the Eskimo area was full and there were available seats elsewhere.

The rule made no sense to Alberta. It also turned other Eskimos against her. When she complained about the restrictions to the manager, she was promptly fired. But, little did the manager know that his actions would be a flashpoint in time, putting into motion a series of occurrences that would forever change the social structure of Alaska.

Determined to fight against laws that denied her people the same freedoms enjoyed by Euro-Americans and also her own unjust treatment, Alberta telephoned the Nome office of an Army major. At her request, he agreed to meet her for lunch at the Nome Grill.

As they sat across from each other that noon, she handed him a theme she had written for class-a logical appeal for justice and equality for the Eskimo people.

After all, the newcomers who discriminated against them had overlooked Eskimo contributions to the Red Cross drive, the fact that they enlisted in the military-as her own brother had done-and supported the Bond Drives.

Impressed by her courage and sympathetic to the cause of the Eskimo, the major urged her to take her theme to the Nome Nugget newspaper. It appeared in the next issue as a Letter to the Editor under Alberta's signature.

The wife of a local store manager wrote a letter attacking Alberta's viewpoint which was published in the following issue. Undaunted, Alberta sent yet another in response, but the "hot button" subject was over with as far as the editor was concerned.

Even as life proceeded as usual, the matter was far from over and continued to simmer among the Nome population. Another incident further stirred the established order when a U.S. sergeant-a Euro-American newly stationed in Nome-invited Alberta to the movies and to sit with him in the "white" area. Management was called. Then the police came. Her "infraction" earned her forcible ejection and would land her in jail.

But Zeitgeist had come as time and destiny met to define an era, and Alberta was the perfect vessel to initiate the change that, for her people, had been far too long in coming: Her aunt, Frances Longley, for instance, was a member of the Arctic Native Sisterhood in Nome, and had direct connections to Roy Peratrovich, the grand president of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. He and his wife, Elizabeth, were equally supportive in battling discrimination against Alaska's Natives.

As civil rights advocates, they had the added advantage of close ties to Territorial Senator O.D. Cochran, his children, and Alaska's governor, Ernest Gruening. All were sympathizers to the Eskimo's plight.

Better still-humiliating and unjust as it was-it was Alberta's treatment at the theater that would spark the Eskimo masses to action. In a coordinated effort, great numbers of them bought tickets, stormed into the theater the following Sunday and sat wherever they pleased.

Details of the incident were wired to Governor Gruening in Juneau, who demanded the mayor carry out a full and complete investigation and report back to him immediately. In a matter of hours, the mayor wired a response: "A mistake has been made. It won't happen again."

The major who encouraged Alberta had previously issued a poignant statement regarding the Eskimo: "Many have served creditably in various theaters during the recent war...They have seen the outside world. Theoretical democracy has been a part of their indoctrination. Can they be expected to return to their Native villages to resume again a position of dumb acceptance of the white man's word or wish as the law of their village?"

Along with Alberta's courage and the crucial testimony of Elizabeth Peratrovich, such statements helped to stir the collective conscience and contributed to the passage of the Alaska Anti-Discrimination Bill, which penalized racial discrimination in Alaska long before the Civil Rights movement took place in the rest of the nation.

In 1955 when Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white patron and sparked a bus boycott in Alabama, Alberta Schenck was belatedly honored as "the Rosa Parks" of her people for her courageous fight for equal rights.

The 2009 movie, For the Rights of All: Ending Jim Crow in Alaska, profiles their struggle, and Alberta's experiences and contributions to the passage of the Alaska Anti-Discrimination Bill.

In 2011, Alberta Daisy Schenck was inducted into the Alaska Women's Hall of Fame.

A version of the above article appears in 100+ Native American Women Who Changed the World, by KB Schaller (Cherokee/Seminole heritage),winner of a 2014 International Book Award, Women's Issues category. She also comments on book reviews for East County Magazine (San Diego). Her books are available through Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-a-Million, and other book sellers. She lives in the Miami-Fort Lauderdale area of South Florida. Contact: soaring-eagles@msn.com http://www.KBSchaller.com

References:

America's Story Website, The Purchase of Alaska

Cole, Terrence M., Jim Crow in Alaska, The Passage of the Alaska Equal Rights Act of 1945, (1992)

Iowa Public Television website, For the Rights of All: Ending Jim Crow in Alaska ( 2009)

Marston, Muktuk, Men of the Tundra: Alaska Eskimos at War, excerpt, Chapter 11, The Beam in Thine Own Eye, (1969, 1972 )

Website, In Loving Memory, Alberta Daisy Schenck Adams

Wikipedia, Alberta Schenck Adams