The '60s "Baby Scoop": A stolen son finds his way home

An interview with Wayne William Smoke-Snellgrove

Last updated 1/17/2015 at 7:07pm

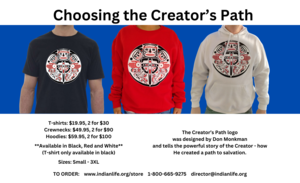

Wayne William Snellgrove

Wayne William Snellgrove (center) with adoptive brother Thomas and adoptive mother, Anne.

"The hardest thing I ever did in my whole life was to grow up."

-Wayne William Smoke-Snellgrove

The tone of my friend Beaded Wing's email was excited: "You really need to talk to this brother and write his story. I've already told him you'll be contacting him."

"Brother" or otherwise, I wondered what he could share that I had not heard before. But, when Wayne William Snellgrove mentioned the term "60's Baby Scoop" during our first telephone conversation, I knew that his story would be as riveting as any tale of fiction in its unearthing of an era largely cloaked in secrecy.

I had heard of U.S. Indian babies being taken without parental consent and adopted out to white couples. My research would reveal a much more expansive practice in Canada as well as the United States.

When unmarried Nora Smoke, a Saulteaux living on a Saskatchewan Reserve gave birth to a son on April 9, 1971 in a Wadena, SK hospital, she named him Dwayne Ivan Smoke. He was born with a cleft lip and palate and would later be renamed Wayne William Snellgrove.

Thirty-two years would pass before Nora Smoke would see him for the first time, and her experiences, common practice in that era, would represent government policies toward Indian babies in our two neighboring countries.

History states that after World War Two-from 1945 to 1972-for the first time in their histories, there was a surge in premarital pregnancies among white girls and women in the Western nations of New Zealand, the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Attributed to a shift in social mores, it was a departure from traditional biblical mandates regarding female chasteness.

Public opinion weighed heavily against such girls and women, and in the United States alone, an estimated four million white mothers surrendered their newborns for adoption. Maternity homes were the trend and seldom was an attempt made to assist young women in keeping and rearing their children, and adoption was usually presented as the only option.

However, for Indigenous heritage babies, adoption had a more sinister spin. From the 1960s through the early 1980s, the Baby Scoop Era-a term coined by author Patrick Johnston-great numbers of Aboriginal babies were simply taken from their families and birth cultures without parental consent.

Indigenous heritage children were then placed in foster care or adopted out, primarily to white middle-class families. Even as late as 2002, according to award-winning journalist Margaret Philp, there were about 22,500 Aboriginal children in foster care across Canada.

"My mother nearly died during my birth," Wayne Snellgrove told me. "She went into a diabetic coma for 31 days. When she recovered and came for me, they told her I wasn't doing well and to come back later. They lied, because they had already placed me in an Ontario orphanage," Wayne Snellgrove stated during our first interview.

The American Indian Adoptees website states that from1971 to 1981, more than 3,400 Indigenous Canadian children were removed from their homes and provinces. More than a thousand were sent to the United States where the demand was high for children to adopt and for every child placed, American agencies received $4,000.

Because the Baby Scoop Era closely followed the phasing out of Canada's residential schools, some view the widespread apprehension of Aboriginal heritage children and placing them in a Euro-structured learning environment as an outgrowth of that system. The mindsets behind both practices was the belief that they afforded the best opportunities for the children to compete in the broader society.

To Wayne Snellgrove and other condemners of the era which ended officially in 1978 with the passing of the Indian Child Welfare Act-it was no less than human trafficking.

"Baby Scoop was part of Canada's paternalistic Indian policies-their attempt to take the Indian out of Indian children by placing them in orphanages, foster homes, and adopting them out to be reared by whites." Wayne Snellgrove remembers being a helpless ward in all three.

"It was government policy back then, a common practice. Their people would come to hospitals or homes on the reserves, knock on the door, and walk away with Indian babies. I was placed in an orphanage till I was four." He has forgotten the number of foster homes.

"There were women caretakers-mother figures-but even though I was too young to figure things out, I knew something was missing, something was wrong. It was a kind of cultural genocide," he says.

Around age three, he was adopted by a white American couple, Richard and Ann-Margaret Snellgrove. They renamed him Wayne William Snellgrove. Richard was a Professor at Penn State, and Ann held a Ph.D in nutrition. A year earlier, they had adopted a son, Thomas. He was white.

"It was a loving home, but I look very Indian, and I knew I was different. I had no sense of permanence. Not knowing what 'family' meant, I lived in fear of being moved again. It was not until I was about ten years old that I realized the Snellgrove adoption was permanent." In 1976, the family moved from Pennsylvania to Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

School was another challenge. "By the time I was seven, I'd had about 20 surgeries, one after the other, to repair my cleft lip and palate. I stuttered, and was given speech therapy. "After each surgery, I would look in the mirror at my swollen lips. I got teased by other kids about how I looked and talked," he said during our second interview session.

Because of his difficulties, young Wayne failed first grade and was labeled learning disabled. The stutter returned, as it did when he spoke of other still-troubling aspects of his life.

"I figured, the way I looked had to be the reason my mother and father had given me away. Why wouldn't they? Even I hated me."

A moment passed before he continued. "I was only seven, but it was then that I made my first suicide attempt."

It would be the first, he stated, of more than three dozen others. But, even as the heavy cloud of despair and suicide hung over his boyhood life, it was also during this period that something miraculous happened.

Around age eight, at the neighborhood pool, he discovered swimming. Trouble was, he did not know how to swim. He failed at his first attempts while other boys left him in their wake as they swam laps.

Instead of discouraging him, losing roused his anger. He pushed and challenged himself until, as a member of the New Jersey Wahoos swim team, he reached the level of Mastery. Swimming became the outlet for his pent-up rage. At himself. The world. And God.

"I swore off God. I figured, if He cared about me, why had He allowed such terrible things to happen? I felt He had done nothing for me."

By the end of his eighth year, the young swimmer had gained national ranking in the eight-and-under age group.

By 1991 he had won many other titles, and would advance to the elite level of U.S. Olympic team member. Due to the hard training he demanded of himself, in time, he would sustain a torn rotator cuff.

In yet another setback, he was also diagnosed with a heart condition and told he should give up swimming. He refused, continued to train, and in the same year, shattered the National High School Record in the 200-yard medley relay.

But other struggles would plague him. Alcohol and substance abuse established a hold in his life. He dropped out of New Jersey's elite Peddie School and entered a detox program. He never graduated Peddie, but in late 1992, would break two YMCA National records, and also win other titles.

"Drugs and alcohol sent me into a downward spiral for a time," he said, "and I tried them all...crack, heroin, alcohol...it had all started as a pastime, but I grew fully involved in them."

He moved about a lot during those years, and around 1992, graduated from Danvers High School in Massachusetts. Based on his swimming performances, in 1993, he was awarded a full scholarship at LaSalle University. He failed out after one term. In the summer of that same year, he began ocean swimming and worked for Atlantic City Beach Patrol.

On a whim, he moved to South Florida in 1994 and lived homeless on the beach for a time. While he searched for work, he continued his training, this time, at the Fort Lauderdale International Swimming Hall of Fame. In 1995, Wayne Snellgrove won the USA Swimming National Championship 5k, Open Water Swim, and several more prestigious titles.

By 1997, he had found work in fire rescue. To maintain his clean and sober status, he continued to attend Alcoholics Anonymous where, he stated, "I learned to depend on God." Sometimes, he listened to sermons in the church where some of the AA meetings were held. As he still does, he also worked in shelters and soup kitchens as a volunteer to help the homeless.

"One day, also in 1997, I was called in to take a telephone call. Even before I answered, somehow, I sensed it was bad news," he said during our third and final session. "My adoptive father told me that Ann, the only mother I had ever known, had died.

"I knew she had been battling cancer. It had gone into remission for a time, but it returned and took her away.

"At her funeral, my once strong, healthy adoptive mother was frail and wasted. Lying in that casket, she looked nothing like the way I remembered her. And as I grieved for her, for the very first time, I could identify the sadness, emptiness and sense of loss that never went away while I was growing up.

"I had been mourning the loss of my birth mother all my life, but had no name for it. My grief at losing another mother was almost more than I could bear. But, it was her passing that freed me to search for who I am."

His voice quivered. "The hardest thing I ever did in my whole life was grow up, and it was only then, at my adoptive mother's funeral, that I allowed myself to grieve, and to accept that it was okay to grieve."

Four years passed, and in 2001, he married Caroline LaFontaine, a Canadian citizen. A son, Alexander, was born to them, but the marriage ended in divorce. "She won custody and went back to Canada."

He'd had a dream, one that had recurred throughout his childhood, that his birth mother was still alive, and was looking for him, too. As the search for his mother continued, in 2002, he found an Internet site that specialized in adoptions and reunions. It was especifically for Indian children searching for their parents.

It mentioned "The '60s Scoop." He had never heard the term before, but everything it described fit his circumstances perfectly. It was run by a private investigator-a P.I. Her one-time search fee was reasonable. Wayne Snellgrove was now ready to act on those recurring dreams and took that first crucial step: he contacted her.

"During that period, though, adoption birth records in Canada were sealed and the only way a searcher could access them was if both the parent and child requested them. And I had no idea where my mother was," he said.

One day in 2003, the telephone rang. It was the private investigator. With tenacity and plying the skills of her trade, she had narrowed the search to only three names. He wrote them down, with other facts of his case. But, as badly as he wanted to find his mother, out of fear, he was unable to act.

"I sat on the information for a whole year. What if my mother did not want me in her life? I could not live with that kind of rejection again."

He brightened. "Then, the P.I. told me that she had already made contact and that my mother wanted me to know that she had never forgotten me. She had been searching for me also for all those years. I cried for three hours."

There were few telephones on the Fishing Lake Reserve where Nora Smoke now lived. He gathered his courage and left a message on one that was used by the community. After 32 years, he would finally hear her voice.

Nora Smoke's call-back came quickly. "She explained the pain of losing me at birth, and how government officials forced her to sign a paper giving me up. It was common practice then. She fled the reserve and went underground to save my other brother and sister."

A few months after their first contact, Wayne Snellgrove flew to Saskatchewan. "I met my entire family for the first time. I had five brothers and sisters. And I thought my mother was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen."

Wayne Snellgrove would later hear that out of hundreds of children who were taken from his reserve, he was only the third to make it back home.

"Out of the thousands taken from their reserves, I was one of only a handful adopted out," Wayne Snellgrove discovered, "and most of those went to whites throughout Europe and the United States. The others grew up in state care. I came to see that the fingerprints of God had been all over my life all along."

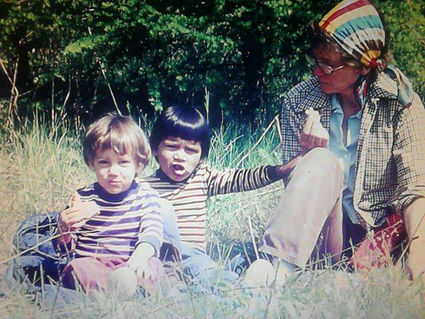

Wayne William Snellgrove

Wayne William Smoke-Snellgrove displays his paintings. He found his mother and he found his way home.

As a Lost Child, Lost Bird, Lost One or Split Feather-as Indian children who search for birth parents are sometimes called-Dwayne Ivan Smoke-Wayne William Snellgrove-finally ended his lifelong search. He had found his mother and he had found his way home.

Wayne William Smoke-Snellgrove still resides in South Florida where he creates all forms of art: paintings, photography, short films, jewelry, and other Native arts. He is also a storyteller.

KB Schaller (Cherokee/Seminole heritage),journalist, novelist and historical researcher, is author of 100+ Native American Women Who Changed the World, winner, 2014 International Book Award, Women's Issues category. Her debut novel, Gray Rainbow Journey is winner of a 2009 National Best Books Award. Her books are available through Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-a-Million, and other bookstores. She lives in South Florida. http://www.KBSchaller.com